A few weeks ago, I got a message from Nerissa Cumpio. “Good morning Sora, the opening will be on September 16th, I hope you are available that day.” For several months, I’d been getting updated photos of the building project progress and finally, the date was set for the (re)opening celebration of Cumpio’s Midwife Clinic! I immediately started to plan my trip.

Rather than fly into Tacloban airport, I decided to make it a bit (more) of an adventure and drive to Leyte. I figured that the cost for gas and the ferry would be comparable to flying and that this plan would allow me to see more of the Philippines, and bring Naomi and Ezekiel with me. Unfortunately, I had a very tight schedule for when I needed to return to Davao, requiring some very long days of driving! Ezekiel decided the long days in the car did not appeal to him, and Matt had classes to teach in Davao, but Naomi came with me, along with Gabriela, one of our friends from Davao.

We set off on Sunday afternoon, well-provisioned with snacks and water bottles. The plan was to drive from Davao to Surigao City on the north-eastern tip of Mindanao, spend the night there, and take a morning ferry, reaching our final destination in Leyte in time for lunch. I had not been able to find a working phone number for the port or the ferry company in order to confirm schedules, but I had the all-important copy of my vehicle’s OR and CR and I had found what looked like a fairly recent ferry schedule on a travel website so I wasn’t too worried.

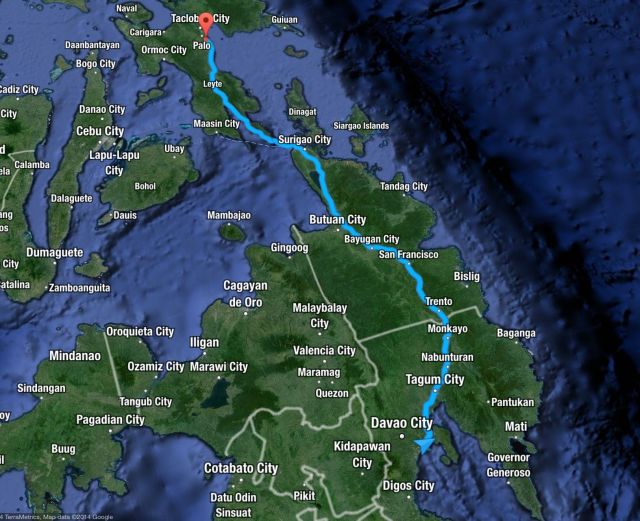

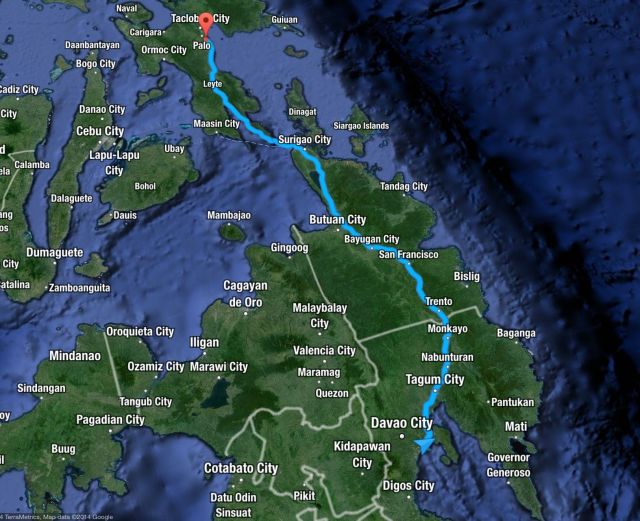

Our route.

The drive from Davao City to the ferry terminal in Surigao City is estimated at just over 5 hours by the google maps app. All I can say, is, whoever created the algorithm for the google maps travel times must never have driven in the Philippines. Our trip was on the Pan-Philippine highway the entire way, but most of the Pan-Philippine highway (outside of the major cities) is only two lanes, and there are frequent landslides and bridge repairs requiring constant maintenance.

Road works ahead.

When road construction limits the two lanes to one, there are never any flaggers directing traffic nor lights at night. And when passing through the numerous small towns the road becomes full of slow-moving tricycabs, bicycles, pedestrians, motorcycles laden with anywhere from four to six passengers plus cargo, dogs, chickens, carabao, etc. (Most of these also have no lights at night.)

Small-town traffic!

Gabriela had been working day shift at the clinic so we did not depart Davao until 2:00 pm. We reached Surigao City around 10:00 pm, completely exhausted. I had planned to go to the ferry terminal before we slept to confirm the ferry schedule and find out how early we needed to show up to secure our place on the ferry, but we were so tired we by the time we were approaching Surigao City that we chose to just check into a hotel and set our alarm for 5:30 am, figuring the ticketing office was probably closed already and that getting to the ferry at 6:00 ought to be enough for an 8:00 am departure. (Rookie mistake!)

We slept well and arose bright and early, headed for the ferry about 10 minutes away. As we got closer, the lines of parked cargo trucks on both sides of the road led me to suspect I might have made a tactical error in not taking the time to visit the port the night before. My inquiries at the port quickly confirmed my suspicion. I was permitted to hand in a photocopy of my vehicle registration to secure my place in line, but not to buy a ticket yet. I was told the morning ferry was already full and the noon ferry was “probably” full as well. The driver of the first car in line to board informed me that he had arrived at the port a little after midnight. Ooops! I texted my friends at the birth camp in Dulag to let them know we would not be there for lunch after all (“Maybe supper, then?”) and we decided to make the best of it by driving around Surigao to see the sights and maybe finding a (more pleasant than the ferry terminal) place to relax for a few hours.

The Surigao beach where we spent most of Monday morning.

We bought some pandesal at a local bakery and found a place where we could rent a beach cottage (picnic table with a roof) for 100 pesos. Naomi played in the water and Gabriela took a nap. We’d been told to check back in at the ferry terminal at 11:00 am, so right on time, we headed over. The ticketing agents were clearly overworked and stressed. When I finally got their attention, I was told my name had been called half an hour before! (I protested that I had left my cell phone number… but that was with a different agent, who had gone off duty in the meantime.) It was okay, we still had our place in line for the next ferry and were allowed to buy our tickets — a multi-step process involving no less than 5 different people all in different offices. I continued to hope for a lunchtime departure though there was no sight of a ferry yet, we parked our car where we were directed… and waited.

The ferry showed up around 2 pm and unloaded. Then the loading process began, and I realized this was going to take a while. The order of priority for ferries is passenger buses (which get on the next departing ferry after they show up), private vehicles (like mine, which apparently usually need to wait a while!) and finally cargo trucks, which explains the lines of trucks on the side of the road leading to the port. And all of these vehicles, crammed as tightly as possible in order to fit as many as possible, are required to back into their place on the ferry… the ramp only works on one side of the boat.

Finally, the ferry’s here!

The crossing itself was pleasant and uneventful, taking a little over an hour. The sea was calm and by leaning over the side into the breeze we could avoid the smell from the large truck full of pigs directly below us. Though there was some nervousness in certain quarters due to the unfortunate ferry accident that had occurred just two days before, I saved all my anxiety for the night driving.

Naomi, enjoying the fresh sea breeze and avoiding the smell (though not, alas, the sound) of the pig truck.

As the San Ricardo ferry terminal came into view, we enjoyed the beautiful views of the sunset over the mountains (the sun sets early near the equator!)

The welcome sight of the Benit (San Ricardo) ferry terminal, late afternoon on Monday.

Unfortunately, we still had 170 km to drive, mostly in the dark, on winding mountain roads. Again, we pulled into our destination around 10:00 pm, tired from a long day of travel. Nerissa and her husband Alex were waiting to meet us at the Haiyan Foodstop, a restaurant built after (and named after) the typhoon. The Haiyan hotel is still under construction but two guestrooms are open, and that was where we were staying for the night. A joyful reunion and a good night’s sleep (with no 5:30 am alarm this time!) and we were ready for the next day’s adventures.